Takeaway: Five Picks at The Armory Show 2018

The Armory Show is a most incorrigible bird. It flaps its wings in such a manner that dust or something falls out with each sweep and you kind of wade through it, acres of scenery, acres of thing. There is a lot to not see at the Armory. Too serious, too interactive, too political. But there are a select few artists at the Armory that are digging in, not out.

Takeaway: Five Picks at The Armory Show

Crystal Palace: The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nuclear Nations: USA (2015)

Ken + Julia Yonetani

Some artists are passing ideas through filters that are themselves and we must celebrate this daring act. We must celebrate the self. Do not be distracted by the tragic-looking and underwhelming spontaneous cloud by Berndnaut Smilde (though I allow the delight to see many a disappointed and confused faces as the fog machine coughed out a few weak puffs after particularly thick hype). Do not worry about the black-lit and neon green chandeliers by one-half of husband-wife art duo Ken & Julia Yonetani, which were regarded by one spectator as "like being inside of a Spencer's Gifts".

We don't mind if you ignore the Tracey Emin look-a-likes and the temporary feeling of the Millennial Pink. Instead, draw your attention to chief moments in art: non-gimmicks; genuine delight.

Sojourner Truth Parsons at Downs and Ross

In what started as a joke, there was something hilariously grim and empty and expensive about Sojourner Truth Parsons' work. My companion and I couldn't pin it- we darted around the idea of it being an appreciation of pets but a uniquely suburban manifestation of appreciation in which pets are praised but still kept as "pets" (as opposed to "children" in certain urban centers). In suburbia, the death of a pet is nearly glamorous with funerals, burials, weeping, then finally the wonderful proposition of a new one.

Help Me, 2016

Maybe it was something like a "suburban funkiness": too-brash colors paired with a daring black, like the interesting couple a few doors down that have perfectly-groomed poodles, two white Volvos, and home loaded with some Rooms-To-Go version of Memphis Design. That is a satisfaction in being an exception, but not truly different. We wanted to move, but Todd's mother needs us around. The dogs, the worthless "cool" furniture, the Volvos. It's an interpretation of giving up.

At once, we spoke to the gallerist (who, when asked, "how are you doing?" responded with, "awful"), to learn more about this daringly specific work. My suspicion was correct: Parsons was dealing with sadness. Her keen sense of usual escape routes was evident. Her energy was forced upon the happy looking dogs. As a Black-Mi’kmaq-Caucasian Canadian, Sojourner Truth Parsons has an extraordinary point of view that only enhances her reception of the mundane and bittersweet reality of life. It's personal, it's funny, and its responsibly executed. Swooping, cartoonish dogs with tongues out and lusty eyes. Hello!

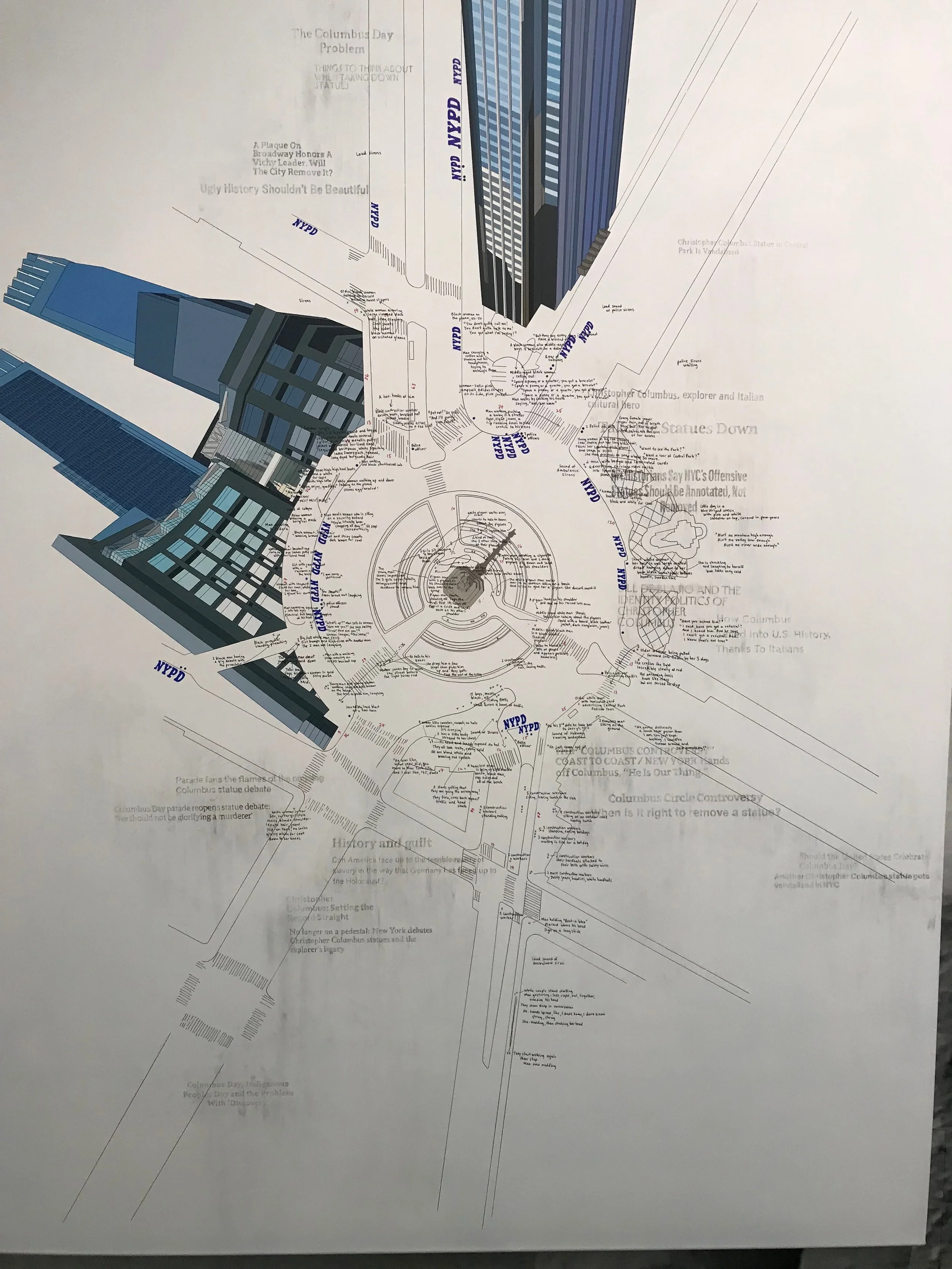

Larissa Fassler at Galerie Jérôme Poggi

Larissa Fassler

I personally undertook a written version of the project that Larissa Fassler has taken to a new height. As presented at The Armory Show, Fassler spent eight days at Columbus Circle in New York City, tracking movements of everything and anything and documenting these on raw maps, in raw text or icons. So much of urban design today concerns itself with the comfort of humans about town. Here is the true examination of birds and people and cars and things, without prompt, but for the personal adventure of seeing things and knowing. There is a regularity here: what happened to Fassler in the span of eight days was probably unremarkable. But here, she has made them remarkable. If you were to have never stepped foot to Columbus Circle, what would you make of these works? Could you infer the regularity of these events? The positioning of the police vehicles (as indicated by the NYPD stamps)? You want the circumstance presented by Fassler to be permanent- in fact, you demand it by looking at the work. But Fassler ties her works back to high level political discussions that seem like a weak appeal to the art world's ever-present "why this, why now?"

But Fassler ties her works back to high level political discussions that seem like a weak appeal to the art world's ever-present "Why this, why now?" Who cares? Let this be the work it is. Do not force a narrative that does not need to exist. Stop timing art. I understood the point in the long-term (read: placing the work in the history of the world) and short term (read: literally, the weekend), but in the vein of works of Nicolas Grenier, Christopher Alexander, Murray Silverstein, and those poets like Barbara Guest that deal in the work of their personal here-and-now in the setting of the impersonal/analytical, there is no need to tie this work back to global concerns and social "needs".

Amalia Ulman at BARRO

Here we are invited to involve ourselves and our concern for the welfare of the participants. A desk- no, an office- a cubical: a single office chair with two red-headed children occupying it simultaneously, both small enough to sit comfortably. They are turned away from you, but they watch a short film on the computer monitor. There is a woman, sitting nearby, scrolling through a cell phone, head down, pant suit, hair messy- communicating boredom or stress. This information is received all at once, and you are immediately faced all of the questions as you contextualize the circumstance: office space. Art show. You begin an internal interrogation: Is this a piece of performance art? What am I looking at? Is those the woman's daughters? Who is the woman? Is it the gallerist? These are her daughters. You contextualize further. No way. The content of the monitor. This is art. They're all part of the art.

This is the genius and elegance of Amalia Ulman's work. You are bothered and concerned and not scared but curious and keen on maintaining distance. What if you make a mistake? You misjudge? The power of Ulman's work lies in your interpretation. You are forced to interpret it for its literal implication, not for what you think the artist is trying to do. You want to intervene. You want to end the piece as much as you want to be a voyeur and walk into it, and study the humans like you want to study humans on the street. You strongly wish to objectify these people as you may believe they are availing you to do so. Or you look inward. You see this. You see it as an anti-capitalism statement. A cog in the machine. It disgusts you but you appreciate it in the context of art. This will show them. There is a sick moment of reliability. I told you I'd hate this baby, and I do, I fucking hate it. You force your stresses onto this work. You reveal too much about yourself in this work. You scratch and claw for any indication of meaning or assignment. Nothing. Two eggs in a nest on an office chair is immediately before you. Office art, quotes. A bird. This is the triumphant and rare moment in art in which the artist has merely set a wonderful, concerning stage for you to feign for yourself and resist any engagement. You want to exit urgently now. The work has troubled you too greatly. It feels like a horror film. It feels hopeless. You are forced to give up looking for any deep meaning and you walk away. The work reveals the primal urges and this is its remarkable power.

Of course, my time there was brief. It may have been purely circumstantial. These children, that woman. Not involved. Highly engaged with the work. Watching "Bob's Movie" on the monitor. This is Bob's office. If you were armed with this information, as I was not, you would find this space heartwarming. Delightfully engaging. You feel invited. Again, it's all about you. "Having moved into an office, she discovers herself as a business woman and adopts a pigeon named Bob, a grotesque alter ego" (quote via Amalia Ulman web-page). Additional resource: SIJBT.

Yukiko Suto at Take Ninagawa

Collected by the very institutions of Japan, do not resist the pensive, empowering views of Yukiko Suto's architectural spaces. Suto is not in the business of hiding things or misleading a viewer. You look at two things at once. In one instance, it is flowers. Brilliantly illuminated. You are looking at districts in Tokyo and Yokohama. Common. Unremarkable. You appreciate these works because you expect everything and nothing from them. You instantly recognize the pleasure the artist has taken in the steady architectural hand- unflinching lines and straightness. The organic satisfaction that flowers and bushes, leaves, brush, wood all contain. You feel serene. And though not completely finished in color, there is enough here to communicate completeness.

You are offered a domain. A space to indulge in. Your own secret garden awaits you. Or, you are just outside of a garden. A fine wall and gate blocks your view. But you forgive the wall as the suspense is nonexistent. You are okay with viewing the garden or not. Because even one flower will be responsibly visualized. Like starvation or a great desire for water, even a drop will please you endlessly.

Further, find delight in the inevitable human tampering with landscapes. You feel okay with this obstruction of nature in exchange for tasteful civility. The land is tamed, tranquilized, but not killed or removed. Houses and fences, walls and gates tiptoe around the flowers and plants. If not, Suto demonstrates a forced, inevitable presence of the flowering power.

Vanessa Baird at OSL CONTEMPORARY

You very desperately want to interact with Baird's work but you don't know how. There is a small temptation to lick the panels. Mostly just rub them. "Are they carpet?" You ask. Triumphant, room-filling work, it is. Great work here. I like this work. Towering above you, falling below you, like very vast and important individual panels in the Chinese tradition. But the Norwegian artist has her first show in the United States, and the work (singular) is calledAn an amazing thing happened to me: I suddenly forgot which came first, 7 or 8. It is discouraged from licking or even rub the work. Do not finger the work. Don't even breathe on the work. The works feel like ancient discoveries, long-rolled into fat mats, tucked into a garage or a storage unit from the earlier centuries.

I don’t want to be anywhere, but here I am. Vanessa Baird

(2015)

In some way Vanessa Baird's work is timeless. From an interview after an award win: "I made huge drawings like wallpaper. A wallpaper like in anyone’s bedroom. At first sight it looks nice and pleasant, like an abstract painting. And then I added Little Black Sambo and his entire family into the wallpaper where they are all drowning. I also included my rather chaotic personal life. Like daily life at home." This frank and appropriate response is even further reinforced by Baird's obsessively straightforward personality. She is about stylish dread. And again, the viewer is invited to get involved as they wish. Control the fractal. Let the zoom happen at will. They are sometimes urgent or curious or hesitant or very dreadful. You know more than the characters depicted.

But here you must see something: intensity manifested through soft pastels. Can you possibly imagine a middle aged woman, scribbling furiously on the floor of her Norwegian home, her old mother not far away. This scene is at once so charming and alarmingly juvenile as Baird has three children. But the work at The Armory, An an amazing thing happened to me: I suddenly forgot which came first, 7 or 8, really is an obsessive internalized analysis of life. Momentous works like this come in a generation. The Unicorn Tapestries. Whatever Bosch was doing. Waterlilies. These expansive pieces are graceful in their coolness. It's like drawing a very big map. The depressing outsider will call it obsession. You will call it a hobby or commitment or validate it as obsession. It's expertise. More accessibly, Baird's work is a release. It's a pleasant time. It's the punching-the-pillow. It's the alcoholism. It's the whatever it is you do to release. To understand and accept circumstance. But it is truly about Vanessa. You're welcome to look.