Periwinkle Bubble Wrap: Denise Treizman and the Art of the Disposable

Editor's Note: Here we are informed by the enthusiastic Anne Whiting, remarking on the shared delight of the disposable, specifically Denise Treizman’s latest solo show, The Marshmallow Method. Ms. Whiting, a student of literature and fashion and a graduate of Parsons School of Design and Boston University. In the entrepreneurial spirit, Whiting is a founder at the art party series The Brooklyn Art House, editor at bSmart.com, and writer at An Inconvenient Wardrobe.

It was supposed to be Spring, but the soft sun of a late March afternoon in Hoboken was tucking itself into the clouds as I followed my little blue dot in search of Proto Gallery. A truck lot to my left, in which a dumpster propped up a sullied, star-shaped pillow with a very happy face on it. Happy trash. A symbolic precursor to the scene I sought on the other side of this desolate end of Willow Avenue: Chilean artist Denise Treizman’s latest solo show, The Marshmallow Method.

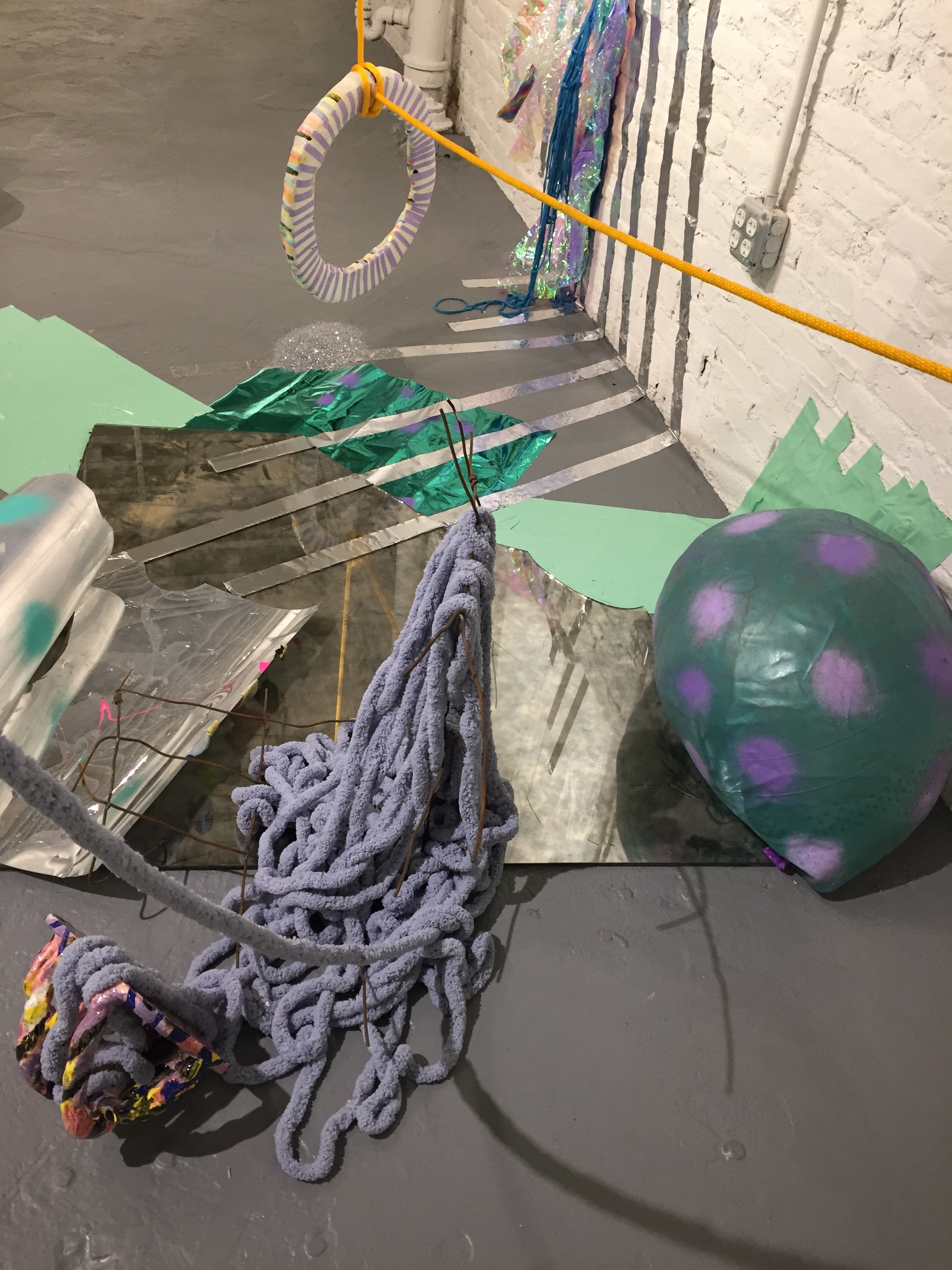

Doorbell. A big hug. I had on a polka dot faux fur coat, which Treizman wondered if I’d worn to match the art. Inside the gallery, final touches being made to a very curated mess: a pile of silver glitter poured on the floor; heavily glossed donut- and sea creature-esque ceramic works scattered throughout assemblages of wrapping paper, construction debris, shiny duct tape, colorful sailing rope, et cetera. A piece of blue and polka dot pottery hung midair—a clay crown, I realized. Inside of its whimsically molded frame, a neon rainbow spiky bouncy ball, deflated and squished into submission.

A mock of royalty? Or just randomness; absurdism?

I vividly remember wandering into Denise Treizman’s main workspace at an EFA Open Studio Night last year. My eyeballs all but drooled tears at the sight of so much neon, sheen and sparkle, at the ingenious incorporation of vibrant everyday items into completely confusing yet charming, immersive, both sculptural and painterly works of “art”. I was overcome with a weak in the knees, short-of-breath type of I love this.

So it was again that I swooned over every compilation of colorful materials and—new to her repertoire—the curvaceous, Medusa-like ceramic shapes peppering the floor. At my bidding, Treizman led me to the pièce de résistance, a massive tapestry she made on a loom during a residency at MassMOCA. It’s woven from silver emergency blanket, hot pink pompoms, royal purple pipe cleaners, neon green rope, gold string, fluffy white cotton (“fluffy wool has my aesthetic”), periwinkle plastic and pool noodles (to name but a few elements- you get the idea), and it drapes from the wall, over a pile of styrofoam, ending on the floor with a spread of zebra-, polka dot-, and neon-colored duct tape fringe. (Because there’s no limit to the array of patterned duct tape one can choose from in the developed world we live in today. What a beautiful thing!) It was as if MaryMe-JimmyPaul wove its scrap “textiles” (perhaps they should enlist Treizman to do this?) into a runner rug fit to line the Hall of Mirrors for a party in honor of RuPaul’s Drag Race.

Denise Treizman makes art with trash.

Originally a painter (self-taught but also boasting education from San Francisco Art Institute, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Central Saint Martins; her silkscreen-like 2D works are also on display at Proto—“Though I consider myself neither a painter nor a sculptor. Maybe a ‘painterly sculptor'”, she muses), it was New York City trash that developed her current artistic language of sculpture and installation composed of art of the everyday, of the throw away.

“[When I came to NY, from Chile, for an MFA in Fine Arts], I remember thinking, Why are people throwing all these things away?”

“I learned it’s New York culture. (It’s…the lack of space) (And no alleyways - Editor). So you know, every day we have these piles of black trash bags [on the sidewalks],” she explains, “whereas, it’s more of a pass-along culture in Chile. Not so much a culture of waste. When you have an old TV, you offer it to others and they take it.”

With the phenomenon of incessant garbage as her visual landscape, she started her Street Intervention series, and went around making art with the garbage on the sidewalks. Like how Duchamp and his Dada contemporaries brought presence to what was almost impossibly “art”, Treizman took to giving life to the dead, spraying or taping neon colors onto black trash bags and neutral-colored industrial waste.

“It was all very ephemeral,” she remarks. Probably because the trash she would adorn would disappear the next day. But the work was also ephemeral in that it was largely undefined, potentially (and imminently) nonexistent—she was splashing her colors onto what people saw as useless or not worth keeping and would likely continue to see as such. So it goes.

She started bringing the debris and discarded items into her studio. Found Objects, she calls them. And then she adds her own touch. Spray paint, for example. Sometimes she uses her own objects, she says, pointing to her old rainbow-striped shower curtain serving as backdrop for an artwork on Proto’s floor.

But as with any new object of which we become fond (or person with whom we become friends), in her finding and claiming of random objects, Treizman bestows upon them importance and utility. They’re no longer trash, but objects with meaning. She knows exactly when and where she’s used and reused each material. “I’ll remember where it came from, because it was heavy, or I remember the interactions I had when I was carrying it, who helped me as I was bringing it in.”

But there’s no object cataloging, she says. She prefers a Death-of-the-Author, often untitled approach to any showcase of her work and lets its individual components do the talking. “Everything [I use] has some meaning to someone;” she says. “One material reminds of something in your life…things that didn’t seem personal because I found it on the street, well, anyone who saw them could relate in an open ended manner…and then someone else can have completely different story with it.”

“The Viewer doesn’t need to know my story; it depends on their relationship with the materials I’m choosing.”

(I, for one, adore a good party, glitter, color, and absurdism, appropriation. Hence my immediate attraction.)

Story is why Treizman at first avoided purchasing supplies in favor of scavenging the street. She sees her pieces as fragments made of fragments: fragments of diverse materials, fragments of diverse meanings therefore.

They’re also glorifications of our excess of arguably superfluous materials. Likely, her work is a study of our taking for granted what as a child she found to be so precious.

(“Really, who needs [bubble wrap] to be purple?” But how lovely that it is, no? We have made art of the mundane, which Treizman has used to make more art.)

Treizman grew up visiting her grandparents who lived in Miami. She recalls how on these trips to America, she could collect and hoard fun things which were unavailable to her in her native Santiago (but things have changed, “of course we have all this stuff there now too”). “I would get the brightest things: pompoms, stickers, tape, pencils. But then I would take them home and I would never used them. I was afraid they would run out.”

But immersion into the land of overabundance—New York—America—led her to realize that not only is there a surplus of material on the street alone, but that she could actually buy more of whatever random material she found that she needed more of. Indeed, we seldom worry about running out in America, not even of materials that are especially made in vibrant colors simply because they can be. (And thank goodness, because then I never have to worry about Treizman’s brightly colored bubble wrap ensconced in gold thread mesh or tinsel not being available for my viewing pleasure.)

[Though one secretly wonders how long we will have available to us such luxurious excess. Best use it while we can.]

This work highlights the fun for the sake of fun, extra for the sake of extra ethos in American consumer culture, incorporating the easy purchase of America’s colorful junk* into her pieces. Because when you need a sponge in the shape of a smiley face, or bright orange duct tape to weave into a tapestry, you can go on Amazon and have it tomorrow. And this, we must never forget, is quite a miracle of the modern first world.

She says the first thing she bought was pool noodle. Indeed, like lavender-hued bubble wrap, it’s ludicrous, hilarious, frivolous, symbolic of pool parties (excess, luxurious) and sunny frolic. It’s also a low cost item, and therefore, at least in American, a disposable one.**

But she still juxtaposes any purchased newness with consumerist waste and decay. (Notice: the pairing of copper duct tape with industrial debris like pipes.)

“My work is…ridiculous,” she says humorously. “I’m a ridiculous artist part of ridiculous society. I need tape and bubble wrap to come in purple, green, silver, with diamonds, flamingos and stars. I’m using what society gets rid of, to only buy more of it for my art…It’s just more nonsense.”

So how does one curate nonsensical artwork which is both rife with meaning and yet a Lockeian blank slate?

Method to madness. A Marshmallow Method, of course. Nick De Pirro, Proto’s man-bun-sporting gallery owner, steps in to articulate the meaning of the show’s title: “I see the marshmallow as a synthetic fruit. It’s something of plant-based origin but which doesn’t actually exist in real life. Denise’s practice is going around finding objects and making them into art. And her new ceramics enter into the mix of Found Objects, acting found because you can never really know with ceramics how it’s going to come out from the kiln. Like with the marshmallow, it’s a fruit that did not exist, but we wanted it to happen…so here is the process of coming up with a marshmallow, which is ridiculous [as a concept] but awesome when done…”

I scribble down the concept, loving the brilliance.

“It’s preposterous and elaborate,” they add.

Like periwinkle bubble wrap.

This is not to say there are no aesthetic intentions at work here. Careful arrangement and display are a must. Treizman’s work suffered a few catastrophes on the way across the river—a woven “drawing” made of string got tangled, some tinsel ripped. And indeed, while anything could go (a gold fringe could be placed either on a ceramic or a drawing compilation) the repositioning various components must be laid out artistically.

It’s abstract art, after all.

And it takes a special eye to make gorgeous, sparkling, lovingly absurd art out of things most don’t (or rather, aren’t trained to, forget to) see as art. With her unconventional use of conventional (though, unconventional conventional—zebra patterned duct tape?!) household (or sidewalk) items, Treizman is painting—allow me the metaphor—with trash. Indeed, how can one argue with the sculptural, painterly quality that is periwinkle bubble wrap and copper duct tape? Obvious yet overlooked artistic elements in what most of us fail to give a second glance. As if we have a right to bubble wrap, when really, how amazing that it exists in the first place. So I’m drawn to Treizman because of how she sees materials as arts themselves. I, too, attempt to walk though life as though it’s a big abstract painting. As a child, I thought I was a brilliant thinker when I coined a phrase I started to live by: “A true work of art is a mistake turned beautiful.” It had something to do with learning, about working out how to make things better than they were before. I still like to imagine that in the grand painting that is my existence, if I make a big ugly smudge here and there, I can rework or cover it up eventually. Anyway, whatever the f$&* it all means, Treizman has certainly made light of what would otherwise seem a questionable overproduction of completely non-biodegradable material.***

Looking at it, one gets a nice dose of joy.

It was still sort of miserably chilly out the night of the opening. But re: above, Treizman watered a budding spring with her sunny, hopeful work.

The opening was lively, hosting a diverse and friendly crew dressed for the lingering presence of winter; subdued, darker hues of peacoats and bomber jackets made the colorful work even more vibrant. (And then there was me. A bright orange turtleneck under the polka dot fur Treizman requested I wear again, bright white running shoes and an ostentatiously studded bag with a big gold chain because I was inspired by Treizman’s concept of ridiculous composition.)

Under the hot pink PROTO sign in the middle of the space perched flowers and cheery cut-out fruits from Edible Arrangements (another modern world marvel). Treizman, in a green velvet dress with a white fur bolero, flitted amongst her fans, her blonde locks cascading her fur like Chilean sunshine gracing the bleak concrete jungle of this side of Jersey. She and her work and its colors are endless summer.

Proto Gallery itself is the refurbished space of a Hoboken-historic leather goods factory, and the right industrial space therefore to illuminate these neons, shiny foils and colorful plastics. Laid back, no frills but the art. Like Treizman had said, Let the art do the talking, I thought, as I reached for a couple of the mini marshmallows dumped on a plate in little fluffy white pile. (Which, I later learned, people were actually scared to eat thinking it might be part of the art.)

Relaxed ambiance. Indeed, how could one not be happy when surrounded by pink ceramic donuts. If I could’ve eaten those, I would have. Treizman’s bright colors, unconventional materials, and proclivity towards that which glistens (few pieces of her work do not incorporate some sort of shine; even the drawings use glitter, or silver spray paint, and the ceramics are thickly glazed so they catch the light and wink back at you) washes away gloom. You can’t help but smile and feel that the only appropriate mood is lightness.

And yet a seriousness—environmental, political—is woven or kneaded or sprayed or tacked onto Treizman’s work. Those who encounter this are entirely at their own fault (yours truly pleads guilty) since Treizman makes no such statements. My dichotomous reactions to plastic are mine and mine alone.****

But personal over-prying aside, the vibe at The Marshmallow Method was cheerful for all those who made the short PATH trip under the Hudson to snack on pretzels, grapes and white wine while contemplating colorful artwork. And the right pre-game to the tiki party I found myself at in the LES after.

I remembered not to step on the little pile of glitter on the floor (Ke$ha should think about collecting) as I made my way back over to the tapestry. Some might ask why? I just say bury me in it.

Ultimately Treizman’s work is whimsy. Because trash sucks, its overabundance is an epidemic that will kill us and the earth, but she makes it beautiful. It’s possible that the next time I’m at Port Authority beelining it to Jersey will be because Manhattan is sinking or poisoned Zombie New Yorkers are out for my Juice Press-ed blood. But for now, Treizman decorates, elevates the industrial. Makes art out of “blah” materials. Gives art to a “blah” landscape.

A smiling star in a dumpster.

That’s a positive and artistic way to live. That’s a mistake turned beautiful. That’s hope. And Faith. And Love.

The Marshmallow Method by Denise Treizman

Until April 29 at Proto Gallery

66 Willow Avenue

Footnotes:

* It is though. Let’s not sugar coat the fact that though Treizman’s materials are marvels of science and production, this stuff is also junk: disposable clutter made of toxic substance that will rot in the ground until it has nowhere to go but up through our nostrils and into our lungs.

** She says her works are not, however, environmental statements.

*** What was that about temporality of trash? Oops.

**** Treizman is one of my favorite living artists, but her work—which for me is so transporting, so joyful, so unique (and ironically so, considering her use of the quotidian)—would not be possible without that which is a culprit for our suffering planet. I question my values, as I love all things shiny and hot pink and would will like to host aforementioned drag party in the Hall of Mirrors.